Workshop + Workbooks

We met at the University of Windsor’s School of Creative Arts for introductions and to discuss our respective approaches to walking, mapping, and land acknowledgment as well as modes of understanding the Detroit River over time. While we started our discussion with early French settler maps drawn prior to the establishment of the Canada-U.S. border, our intention was to see beyond the cartographic signals that prompted patterns of settlement and the eventual division of national space along national lines as we have in the present-day international border.

As collaborative research, the workshop and series of walks enabled us to trace not merely how the international border came to have cultural and political meaning over a century and a half, but more importantly, how to imagine this location without it, and to consider forms of situated knowledge that provide a radically different orientation and ontological relationship to the system of waterways at the bottom of the Great Lakes. This is a complex space: As one of the longest continuously inhabited regions in North America, it is a space of meeting, of transit, of migration, conflict and displacement. It is also a space of colonial and contemporary violence.

To consider Detroit and Windsor beyond the border requires a cognitive departure from global and national politics as well as modern mapping conventions that underpin our contemporary lifeworld. However distant the cultural politics of the 1990s may seem now, the echoes of borderlands discourse, which drew attention to the affective economies of borders through the work of Gloria Anzaldua and others, has emerged again in the work of the Metis artist-activist-scholar Dylan Miner who reads Anzaldua’s work in describing the Detroit-Windsor region as “La Otra Frontera”: the other border to pull indigeneity into the center of a borderlands sensibility in this part of the world. Miner's work also echoes that found in James Red Sky’s Migration Map (1960) which emphasizes the ancient importance of the Great Lakes waterways as being at the centre of the Anishinaabe and Metis lifeworld. It was clear from the perspective afforded by spending much of our time on the Detroit River that this place is best understood not from either shore (as directed by the border) but from its center.

This shift in perspective swiftly re-orients the directionality of the region, away from the static North-South axis of the Canada-U.S border, toward a fluid and embodied sense of the place that Anishinaabe peoples of the Three Fires Confederacy (Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potowatomi) call Waawiiatanong Ziibi (where the river bends, Russell Nahdee). Anishinaabe Elder and Educator, Mona Stonefish has often addressed the importance of water in terms of historical continuity and as a shared ecological responsibility in her ceremonial water walks here, drawing attention to the Detroit River as a point of connection between the Great Lakes, rather than a point of division.

As a form of public history, the workshop and walks focused on the concept of a “stratawalk” to sense and observe the layered narratives encoded in the built environment as well as the sounds, smells, and sights that traversed the river border. Our walks were attentive to the multiple narratives that shape the region, reading between the lines of the border to focus on what does not pay attention to it and drawing attention to the various ways in which the Detroit River serves as a point of connection rather than division.

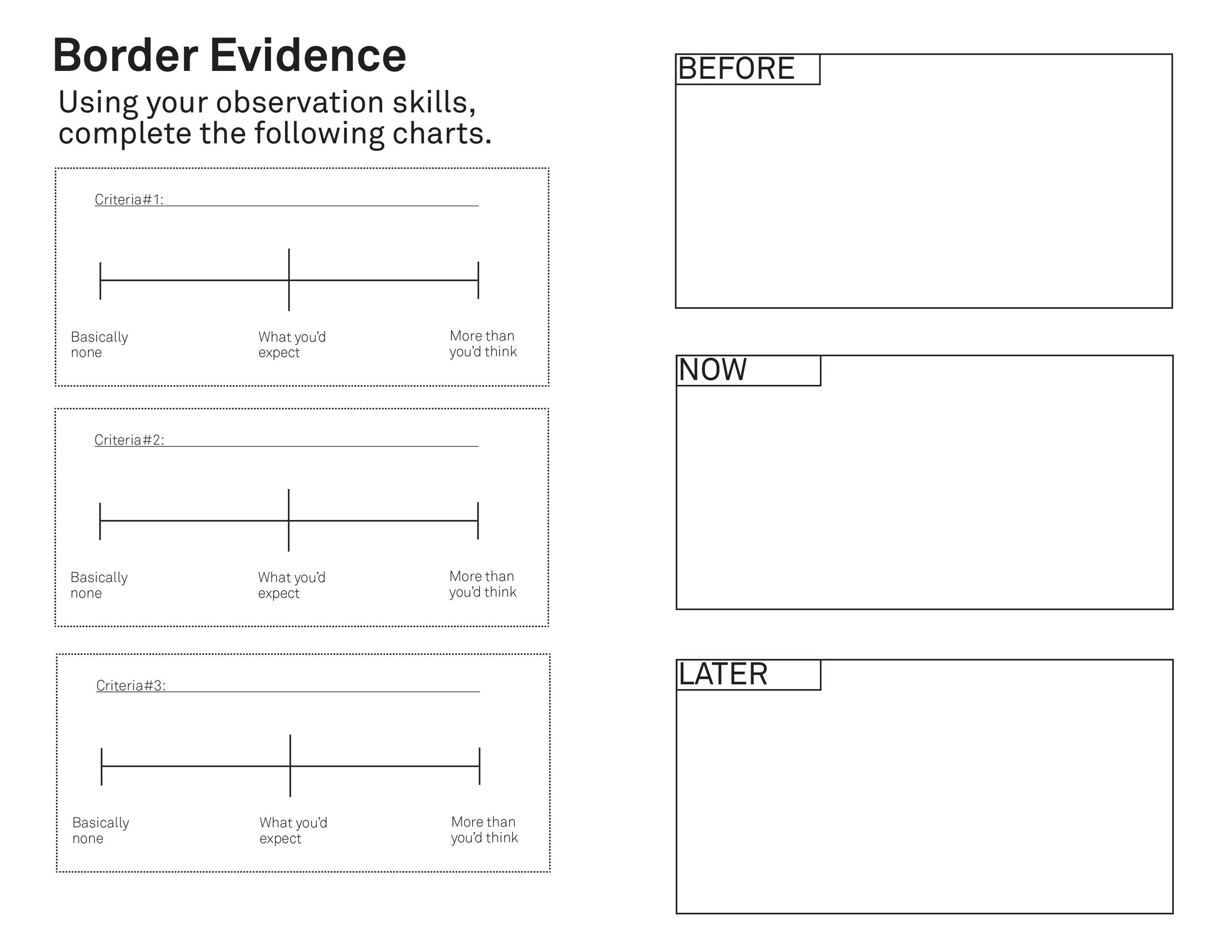

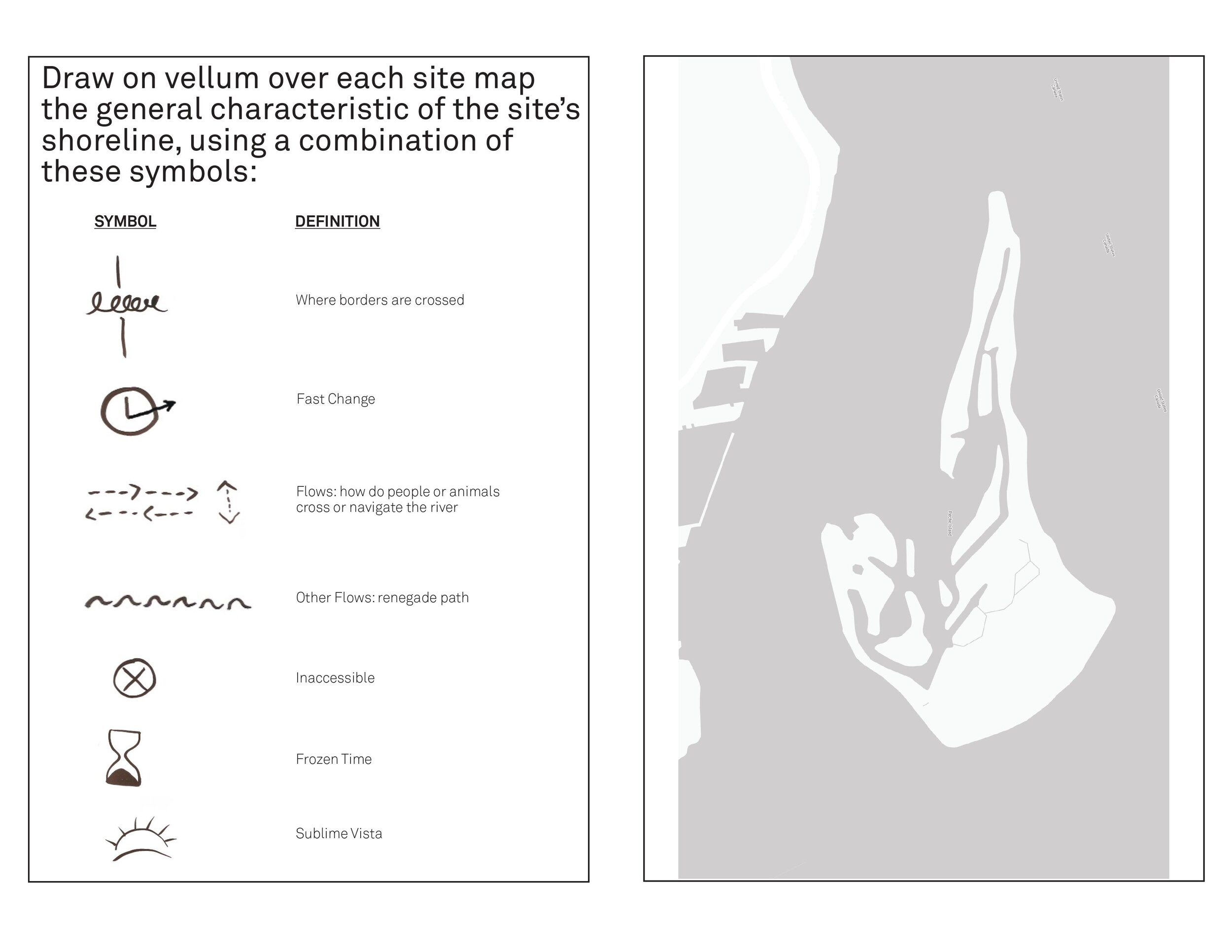

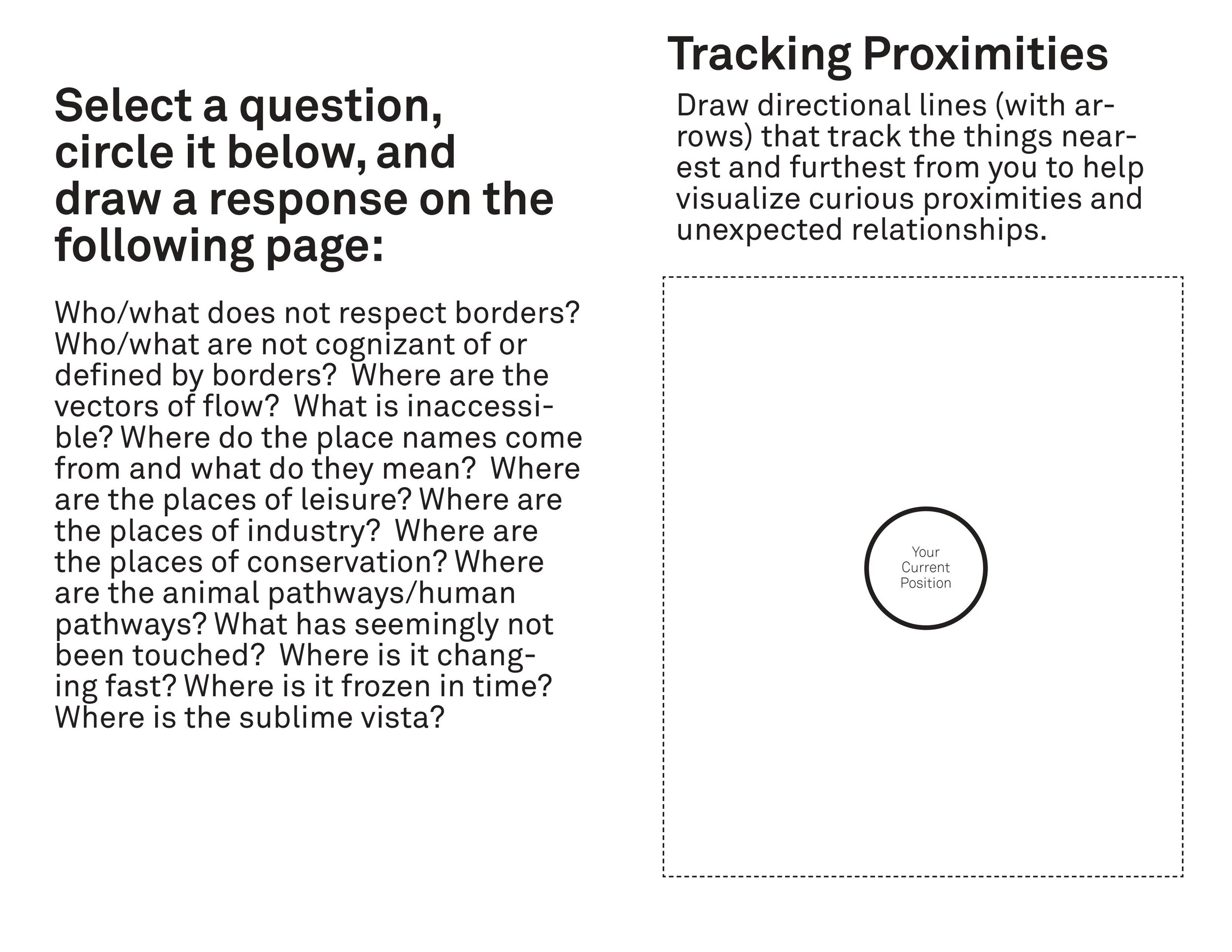

We made workbooks for each of the three locations to prompt participants to record observations of relationships between things that may not be directly correlated to the border. The resulting maps submitted by participants constituted a temporal impression of the various borders, boundaries, and orientations that our three walking tours traced.

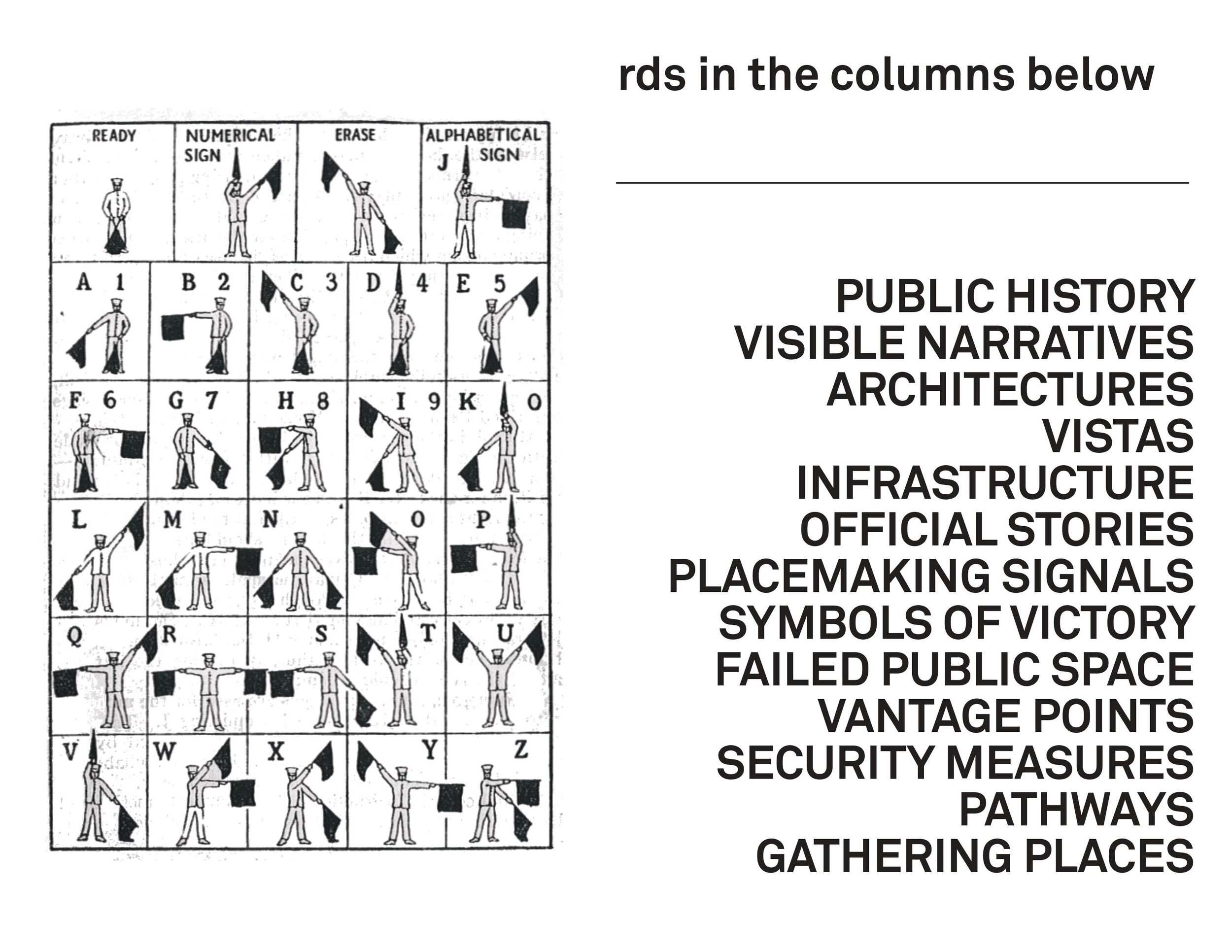

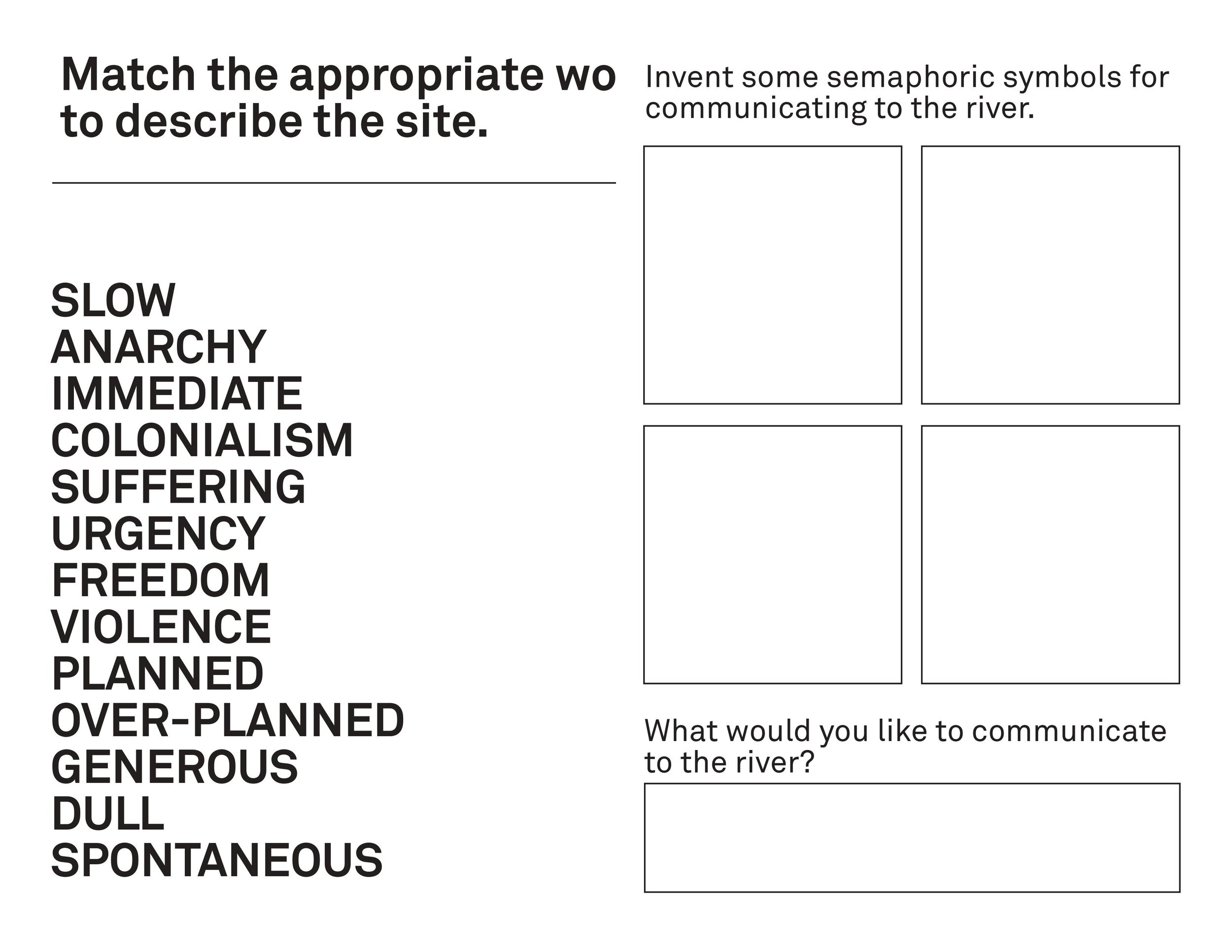

The workshop and walks centered on the idea of water communication through the use of semaphore flags to suture together the three tours (lead by three different groups). The design of the flags corresponded to the disjointed shores of the Detroit River at the site where the new international bridge is being constructed. It is a site of ecological destruction and political controversy. The semaphore is one of the most basic (albeit military and colonial) kinds of territorial marking and communication devices, but in the context of the workshop, they offered a means to performatively mark the locations and trails of migration in ways that bear no relationship to the current picture framed by the Canada-US border.

The semaphore flags enabled us to record our visits in terms of the missing pieces on the map or in the built environment and to mark the places where multiple, sometimes contradictory narratives needed to be held in suspension. The flags enabled a pause, a prompt to leave space to consider what cannot be mapped through conventional cartography. These pauses suggested locations that might be held open to facilitate various forms of unlearning. Buoyant Cartographies enabled a form of deep mapping as a collaborative and performative process. Taken together the three walks provided a range of vantage points to detect the ways in which three centuries of European settlement and colonial allotment have preceded the contemporary surveillance state; But perhaps, more importantly, they led us to consider how place-based knowledge is lost through bordering systems and practices.